I don’t recall exactly when I found out that we were part of Generation X, and that my parents were Baby Boomers. It was probably in the late 80s. In any case, it was never really important to me until I got old enough for nostalgia – probably my 20s – and I started seeing all these kids stomping around like they were part of my generation. It bothered me because they were wrong and pretentious. And it was then that I realized that I grew up in a time, and that that time was unique to my age group, and furthermore that the time a person grows up in potently affects their identity and social expectations. I also realized, because times had changed, that I was proud to be part of Gen X, and a bit territorial about it, too.

Not long after, I learned that the “kids” were actually part of Generation Y. They had learned that by then, too, so I was happy to leave the matter alone for about a decade. But then I had kids. I knew they were too young to be part of Generation Y – which had, by then, been largely relabeled with the term “Millennial” – and that got me wondering about Generation Z. So I went digging again, this time with an eye on historical context.

If you do an internet search on “generations” you will quickly stumble onto the theories of Karl Manheim, and William Strauss and Neil Howe. Without going into much depth, both theories describe generations, or cohorts, in terms of shared socio-historic context. Strauss and Howe add to this the idea that each cohort spans approximately 20 years, and that their respective attitudes and identities cycle every saeculum in a generally predictable way. (A saeculum is the amount of time it takes to completely replace a given human population; approximately 80-90 years). They have described much of American history in these terms by dividing it into cohorts that span from 1433 (the Arthurian Generation) to the present day.

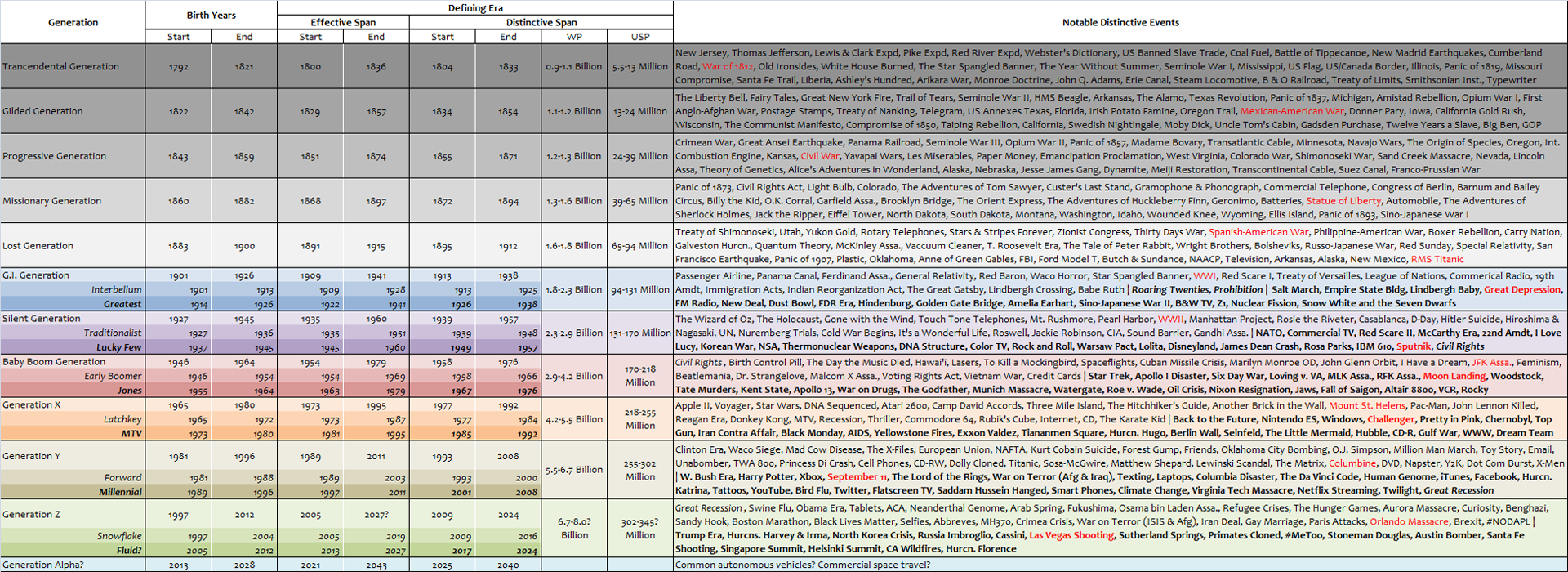

I have relied on the naming convention of the Strauss-Howe theory up through Generation X, and their birth-year divisions up through the beginning of the G.I. Generation, which began with those born in 1901. For subsequent divisions, I have followed suit with the Pew Research Center, largely because they agree with my own observations about cutoff dates, particularly as they pertain to Generations X and Y. I have not conformed to either model in the naming of Generations Y or Z, however, because I recognize “Millennial” as a subset of Generation Y, and I think it’s premature to settle on a name for Generation Z, since the oldest of them are just now coming into adulthood.

I didn’t come up with the idea of generational subsets, but I may be alone in formally applying them to specific birth ranges within each generation. The G.I. Generation (b. 1901-1926), for example, comprises the Interbellum Generation (b. 1901-1913) and the Greatest Generation (b. 1914-1926). These two subsets shared the Roaring Twenties and the Prohibition, but WW I was likely more influential in the development of the Interbellums than it was to the Greatest Generation, which was overshadowed by the Great Depression. To account for intra-generational nuances, I have divided every subsequent generation in a similar way.

If you poke around the internet or the library, you’ll find that the subset appellations I’ve got are already in use, up through Generation X anyway. I’ve assigned Millennial to the second half of Generation Y (b. 1989-1996), because they grew up after Y2K; during the W. Bush Era, September 11, and the Great Recession. This period doesn’t adequately capture the time or the attitudes of those in the first half of Generation Y (b. 1981-1988), because they grew up during the Clinton Era, the Columbine Massacre, and the Dot Com Burst. I have called this subset the Forward Generation, due to their reputed social audacity, and because they constitute the front line of the global technological revolution ushered in by the World Wide Web.

You will notice that we’re already through the first half of Generation Z, which I have tentatively called the Snowflake Generation (b. 1997-2004). I didn’t come up with term Snowflake, of course, and some may object to its disparaging tone. But it matches up well to a lot of broad-stroke characterizations of those that grew up during the Obama Era, the Refugee Crisis, and the Orlando Massacre, so I’m sticking with it for now. The second half of Generation Z – which I have tentatively called the Fluid Generation (b. 2005-2012) – came on line with the Trump Era. That means anyone under 6 years old is part of Generation Alpha; who can say what will define their time?

Now, a word or two about how I’ve organized the summary table. Generations are organized by color; subsets are shown with hue variations. The second subset is in boldface so it can be easily correlated with the boldface words in the Notable Distinctive Events column. The Effective Span in the Defining Era category shows my reckoning for the span of years that affected the social development of each cohort. These intervals overlap those of the cohorts before and after, though, so I carved out Distinctive Spans that are unique to each. The estimates for world population (WP) and US population (USP), and the Notable Distinctive Events are all restricted to the Distinctive Spans. The entries shown in red are what I consider to be defining moments or events.

A quick aside: the Notable Distinctive Events were selected from what is now a very large spreadsheet, so if I missed one you think is important, I probably have a record of it. If there’s interest, I may post up the long list one day. It’s really interesting, to me anyway.

-G

References

Dimock, M. 2018. Defining generations: Where Millennials end and post-Millennials begin. Pew Research Center.

Howe, N. and W. Strauss. 1991. Generations: The History of America’s Future, 1584 to 2069. New York: William Morrow & Company.

Mannheim, K. 1952. The Problem of Generations. In Kecskemeti, Paul (ed.). Essay on the Sociology of Knowledge: Collected Work, V. 5. New York: Routledge, pp. 276-322.