Part One:

Due to apparent disparities between archaeological, linguistic and radiometric evidence, the historical anthropology of the Bahamas, and the Caribbean region in general, remains uncertain. It is generally understood that the Caribbean was settled in waves, first by peoples originating in Central and South America, and later by peoples originating in Western Europe and Africa, and that each wave of immigrants replaced or displaced extant populations by some combination of diffusion, assimilation, brutal conquest, slavery and disease.

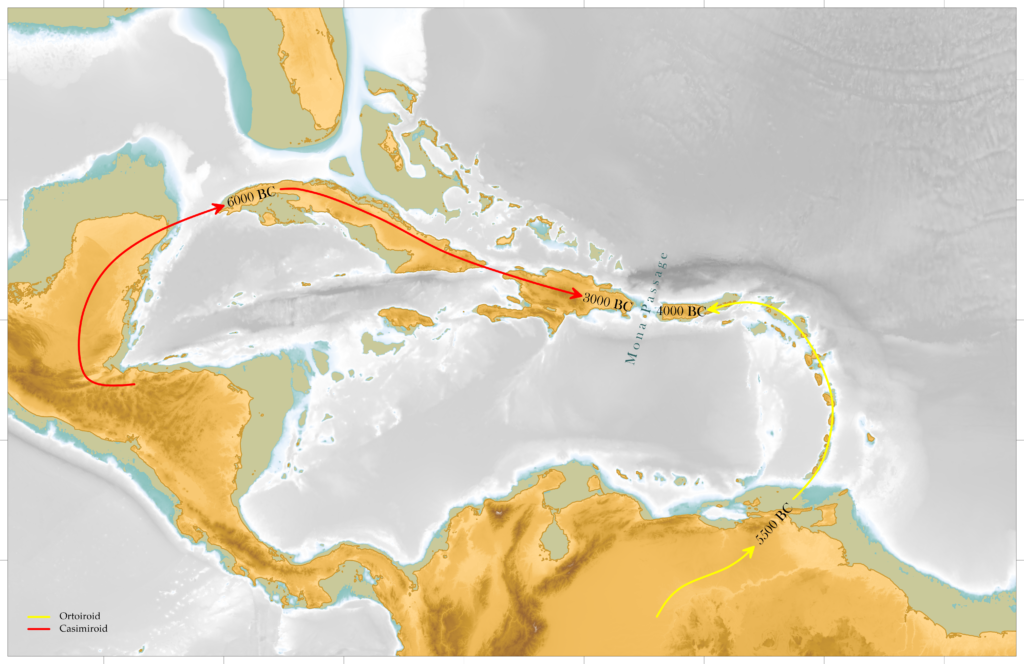

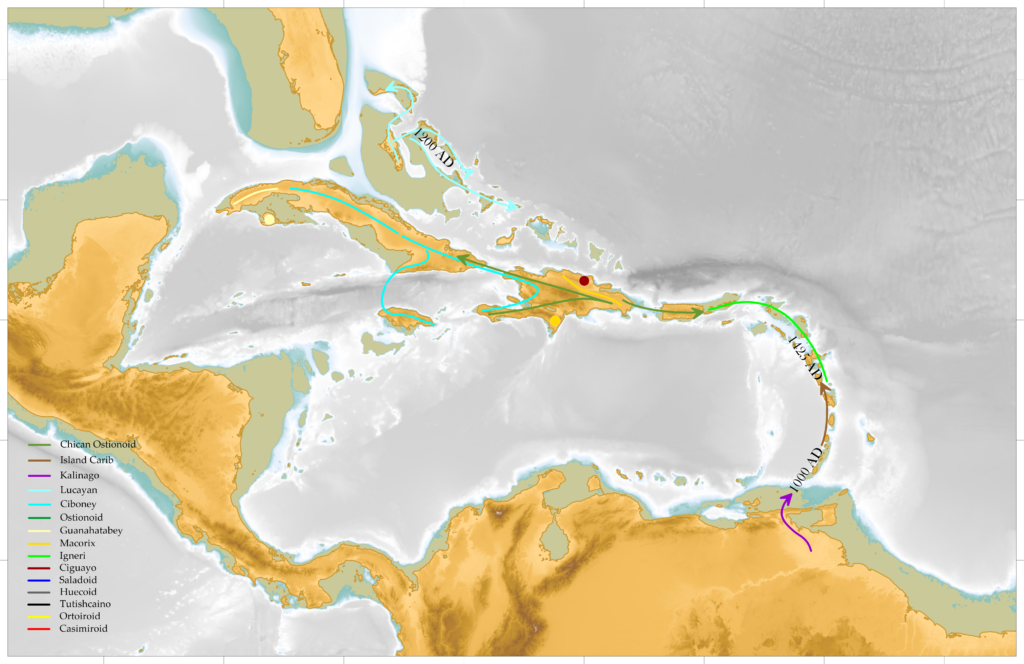

By approximately 6000 BC, a Tolan-speaking people of the Casimiroid cultural tradition (Casimiroids hereafter) began migrating into Cuba from Belize/Honduras via the Yucatan Peninsula (Granberry and Vescelius, 2005). These hunter-gatherers were the first settlers, or aborigines, of the Greater Antilles. By 5500 BC, a Waroid-speaking people of the Ortoiroid cultural tradition (Ortoiroids hereafter) with Venezuelan provenance had migrated into Trinidad, which was, at that time, still connected by land to South America across the Columbus Channel (Saunders, 2005). These hunter-gatherers were the aborigines of the Windward Islands of the Lesser Antilles.

Over the following millennium, the Ortoiroids seeded distinct communities as they subsequently spread northward into the Leeward Islands and Puerto Rico, which they had reached and settled by approximately 4000 BC (Ramos, 2010). The Casimiroids, meanwhile, had expanded eastward into Hispaniola, and though they had established a modest presence in Puerto Rico by 3000 BC, the Mona Passage seems to have constituted a lasting and stable frontier until approximately 1000 BC (Rouse, 1992; Granberry and Vescelius, 2005; Ramos, 2010). This frontier was permeable, however, and over the centuries, the Casimiroid and Ortoiroid cultures diffused across it – materially, linguistically and, perhaps, biologically (Granberry and Vesceliius, 2005).

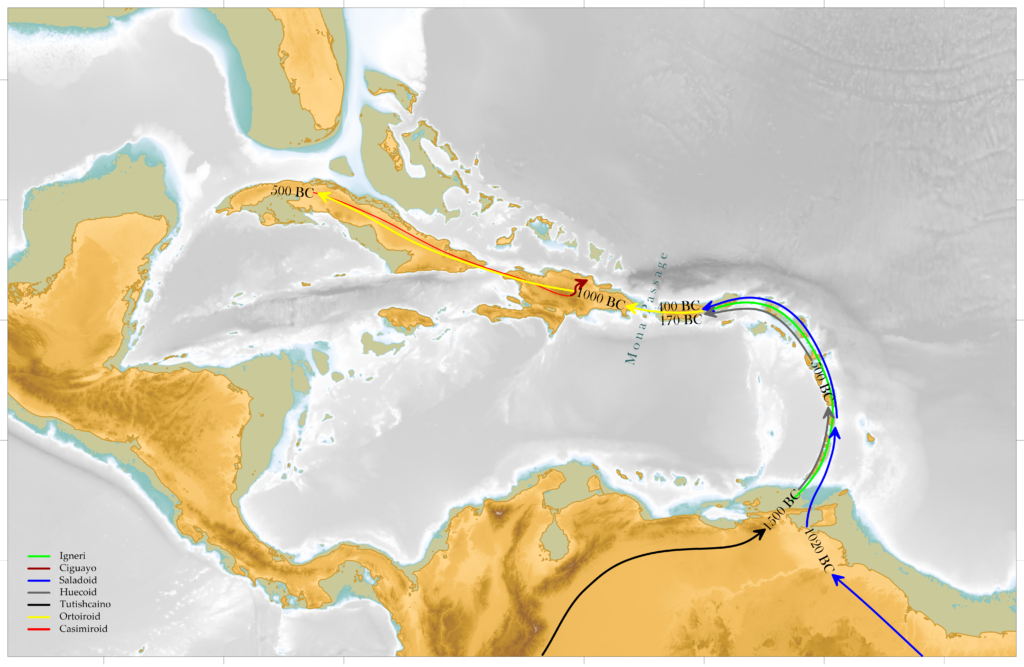

Beginning around 2000 BC, offshoots of the Tutishcaiño peoples in Bolivia began migrating to the north and northeast along the Andean front, ultimately reaching coastal Venezuela (Ramos, 2010; Keegan et al., 2013) by approximately 1500 BC. These ancestral Huecoids were pottery-makers and farmers, and they were joined near Trinidad by another agroceramic culture by approximately 1020 BC (Ramos, 2010). These people were Arawak-speakers of the Cedrosan Saladoid cultural tradition (Saladoids hereafter). About this time, the Ortoiroids began crossing the Mona Passage into Hispaniola, and the Casimiroids subsequently receded into the island’s northern quarter, becoming the ancestral Ciguayo people (Rouse, 1992; Granberry, 2005).

By approximately 500 BC, the Ortoiroids had – excepting the Ciguayos – almost completely subsumed the Casimiroid tradition in the Greater Antilles. About this time, the Huecoids began migrating into the Windward Islands, and the Saladoids followed close behind them. Although these two peoples had cohabited the same regions of Venezuela and Trinidad for some 500 years, they apparently remained culturally distinct as they spread across the Lesser Antilles. In short order, however, the Saladoids emerged as a dominating influence that displaced and hybridized with the Ortoiroids in the Lesser Antilles, creating there the ancestral Igneri people (Keegan, 2013). In less than a century, the Saladoids reached Puerto Rico and, by approximately 170 BC, the Huecoids had arrived there as well (Saunders, 2005; Keegan, 2013).

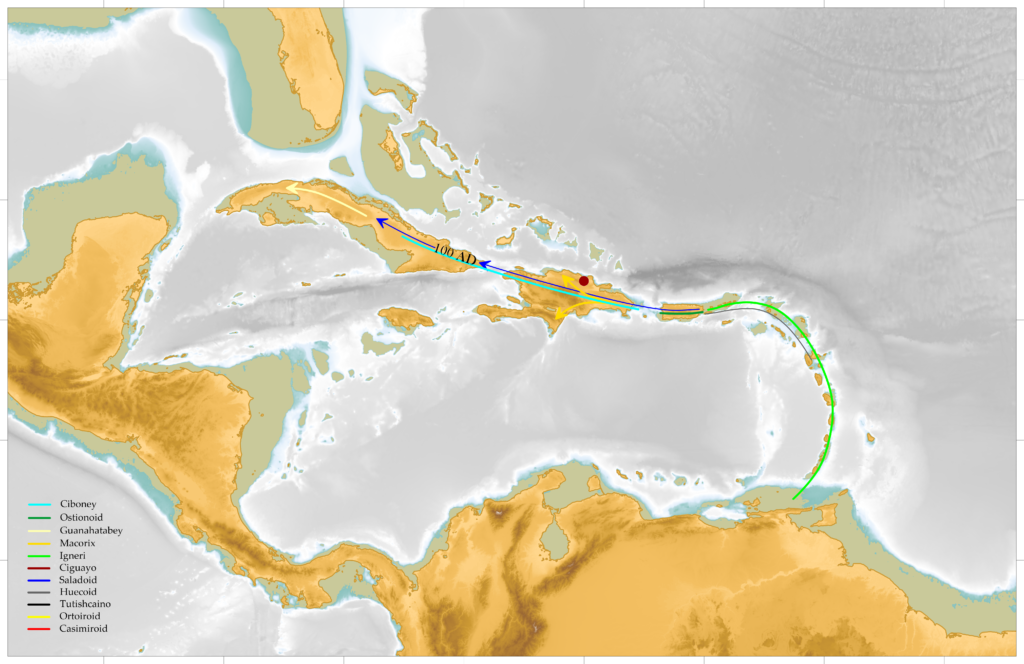

Over the following two hundred years, the Saladoids expanded further westward, first into Hispaniola, and then, during the first century AD, into Cuba (Granberry, 2005). A distinct Ortoiroid tradition was thereafter represented in the Greater Antilles only by the Macorix people in northern and southern Hispaniola, and by the Guanahatabey people in western Cuba (Granberry, 2005; Ramos, 2010). The remainder, and perhaps the greater part, of the Ortoiroid population instead hybridized with the Saladoids and Huecoids in Puerto Rico, producing there the ancestral Ostionan and Elenan (Ostionoid) cultural traditions, and with the Saladoids in Cuba and Hispaniola, producing there the ancestral Ciboney people (Curet, 2005; Granberry, 2005). By approximately 200 AD, representative populations of distinct Saladoids and Huecoids had, like the Ortoiroids, all but disappeared (Ramos, 2010).

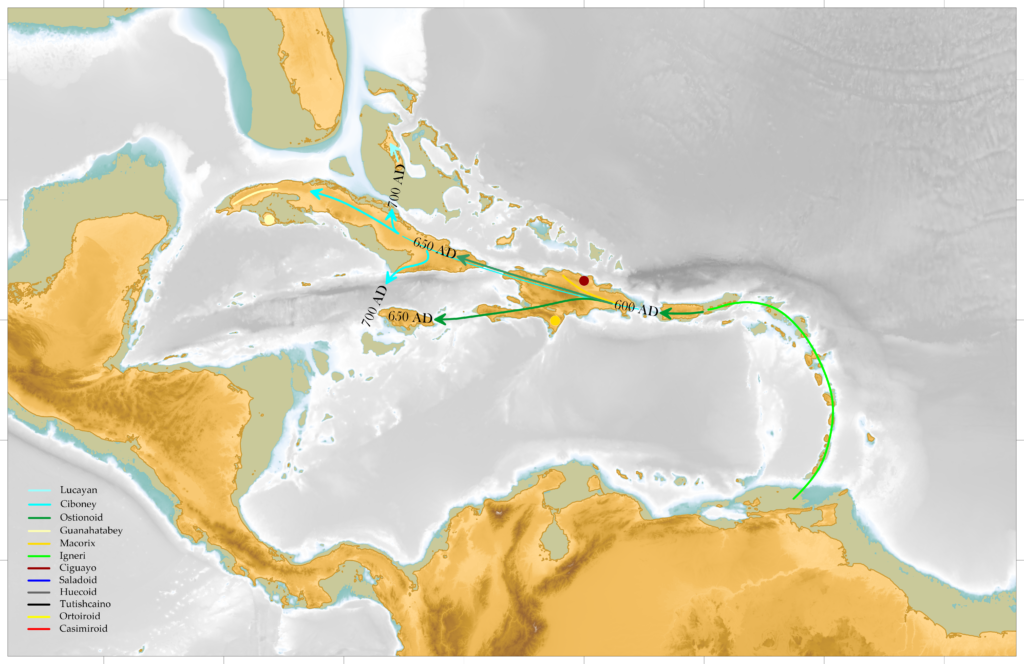

The Ostionoid and Ciboney cultures continued to evolve, apparently in situ, until approximately 600 AD, when the Ostionoids began to expand out of Puerto Rico, first into Hispaniola, and then into Cuba and Jamaica (~650; Curet, 2005). As the Ostionoid culture expanded, the Ciboney that were not incorporated or exterminated largely withdrew from Hispaniola and eastern Cuba and, around 700, began migrating northward to become the aborigines of the Bahamas, the ancestral Lucayan people (Berman and Gnivecki, 1991, 1995). Throughout the Antilles, these cultures apparently increased in mutual trade and developed distinctive agricultural, linguistic and political structures over the following few centuries: the (Waroid) Guanahatabey in western Cuba; the (Arawakan) Ciboney in central Cuba and Jamaica; the (Arawakan) Lucayans in the Bahamas; the (Waroid) Macorix in northern and southern Hispaniola; the (Tolan) Ciguayo in northwestern Hispaniola; the (Arawakan) Ostionoids in central and eastern Hispaniola, Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands; and the (Arawakan) Igneri in the Lesser Antilles.

In approximately 1000 AD, another wave of immigrants began making their way into the Lesser Antilles from the northern coasts of South America (Soto, 2008). These Kalinago people were primarily gatherers and fishers that raided Igneri villages in war parties, commonly killing the men and kidnapping the women. Due to their warrior culture, boys were, after a certain age, raised exclusively in the company and tutelage of men, but all of the children were initially socialized by the women (Granberry, 2005). Thus did the Kalinago begin to hybridize with and subsume the Igneri as they advanced northward, producing the ancestral Island Carib people en route.

By approximately 1200 AD, the Lucayans had spread throughout the Bahamas, and the Ostionoids had developed their agricultural and societal efforts into regions and structures never before attained. Hispaniola became organized as a collection of socially stratified chiefdoms with villages nucleated by political and religious centers (Curet, 2005). Over the following two-hundred years, this Chican Ostionoid cultural tradition spread to the east and west, from Saba to eastern Cuba (Granberry, 2005). Meanwhile, the Island Caribs had continued their northward advance, and by approximately 1425 had reached the Leeward Islands.

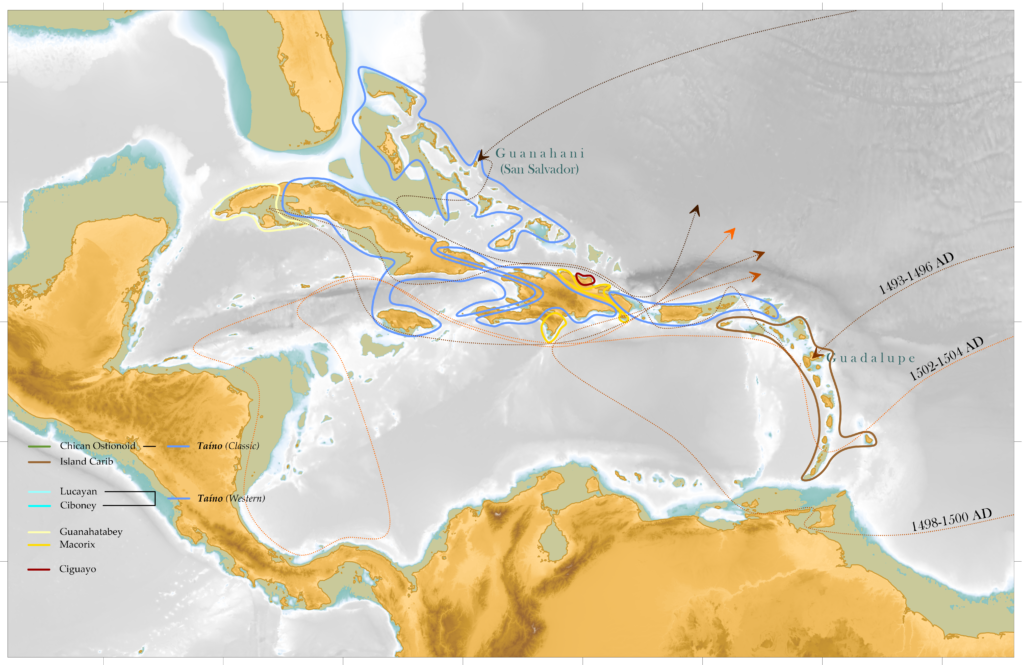

It was into this cultural context that Christopher Columbus unwittingly stumbled when his Spanish ships came to Guanahani (San Salvador Island) in 1492 AD. There, he met the Lucayans, whom he called Indians because he believed he had reached India. He then ventured to Hispaniola, where he found gold, and declared himself the island’s governor. Although the cultural heritage of the aboriginal Lucayans in the Bahamas differed from that of the indigenous Chican Ostionoids – the majority population – in Hispaniola, they were grouped due to their linguistic similarity (i.e. Arawakan), and referred to as the Taíno Indians (Taínos hereafter); the endemic Macorix and Ciguayo peoples remained distinct due to their linguistic differences (i.e. Waroid and Tolan creoles). Initial relations between the Spaniards and Taínos were friendly, but when Columbus departed for Spain in 1493, he took some Taíno with him and left some of his men behind.

When Columbus returned later that year, he did so by way of Guadalupe, where he encountered the Island Caribs, and noted their comparatively hostile disposition. He then went on to Puerto Rico, where the first skirmish between the Spaniards and Island Caribs transpired, reportedly over the latter’s castration of two Taíno boys (Phillips and Phillips, 1993). From there, he returned to Hispaniola, and found the corpses of the men he had left behind earlier that year, slain during conflict with the Taínos. During this voyage, Columbus determined that the native peoples of the Caribbean would constitute a useful labor force.

Despite the Crown’s refusal, Columbus began to subjugate the Taíno in Hispaniola under a forced-labor campaign bent on the growing of sugar cane, the mining of gold, and ultimately the slave trade; slavery was then, and had been for centuries, a common and profitable practice throughout Mediterranean Europe, the Maghreb, Arabia, and elsewhere. The mismanagement and brutality with which Columbus oversaw this effort stirred up rebellion amongst the Spanish colonists, however, and the Spanish Crown removed him as governor of Hispaniola and imprisoned him in 1500 AD.

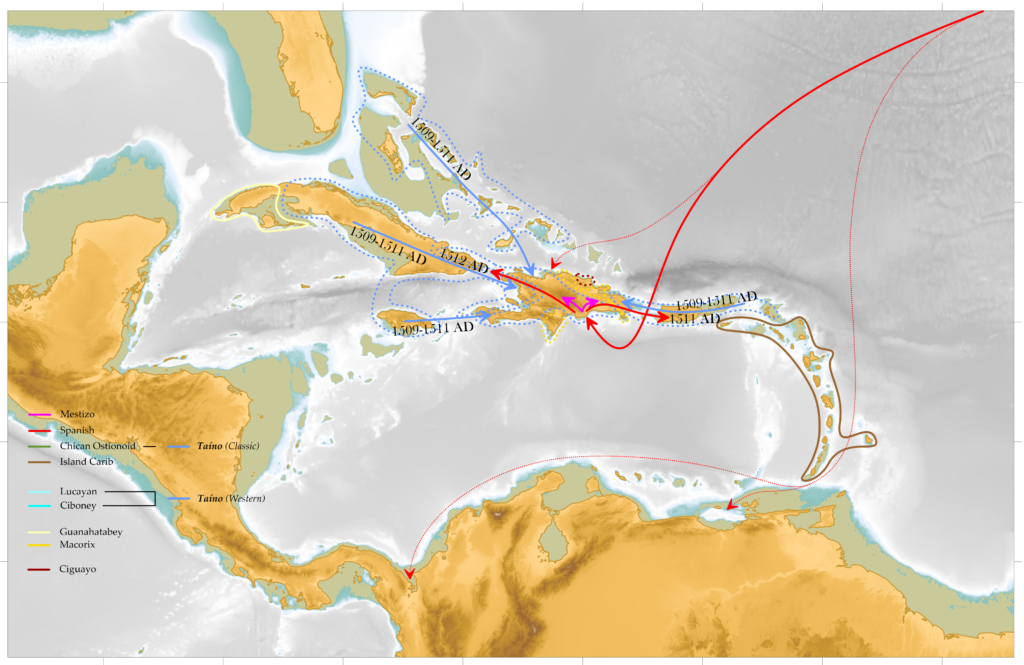

To prevent such abuses of power, in 1503 AD, the Spanish Crown instituted the encomiendas system in Hispaniola, whereby groups of Taínos were assigned to various Spanish officials, ostensibly trading their labors in the fields and in the mines for protection and education. This system soon devolved once more into one of forced tribute and slave labor. At the same time, Old World diseases – to which the native Caribbeans had no immunity – began to spread throughout the Taíno population, proving fatal to most (Zinn, 2003). By 1507, the Taíno in Hispaniola had diminished from more than 1 million to some 60,000 (Sale, 1991).

In 1509 AD, the Spanish Crown ordered that natives be imported to Hispaniola from the surrounding islands to compensate for this population loss. Over the following two years, the Spanish would ship almost the entire Lucayan population – some 40,000 people – from the Bahamas to Hispaniola (Morsink, 2015). In 1511, the Taínos and Island Caribs in Puerto Rico united in an effort to resist the Spanish, but they were ultimately suppressed by governor Juan Ponce-de Leon. The following year, Taíno chieftain Hatuey – considered now a national hero – was burned at the stake after warning the Taínos in Cuba of the imminent Spanish invasion there (Las Casas, 1999).

Thereafter, in spite of numerous laws and pronouncements from the Spanish Crown governing the encomienda and forbidding mistreatment of native peoples in the New World, the Taínos – i.e. the Ciboneys in central Cuba and Jamaica, and the Lucayans in the Bahamas (the Western Taínos); and the Chican Ostionoids in eastern Cuba, Hispaniola and Puerto Rico (the Classic Taínos) – the Ciguayos, the Macoris, and the Guanahatabeys all rapidly declined. Many of the native women in Hispaniola had been taken as wives by the Spanish colonists – producing there the creole Mestizo people in much the same way that the Island Carib had developed from the Kalinago and Igneri peoples in the Lesser Antilles (Guitar, 2000) – and the smallpox epidemic in 1518 AD wiped out some 90% of the remaining native inhabitants of Hispaniola. By 1520, the Lucayans were extinct, and by 1548, only 500 Taíno survived in Hispaniola (Mann, 2011).

-G

References

Berman, M.J. and P.L. Gnivecki. 1991. The colonization of the Bahamas archipelago: a view from the Three Dog site, San Salvador Island. Proceedings of the Fourteenth International Congress of the Association for Caribbean Archaeology. Edited by: Cummins, A. and King, P. pp. 170–86. Barbados: International Association for Caribbean Archaeology.

Berman, M.J. and P.L. Gnivecki. 1995. The colonization of the Bahama archipelago: A reappraisal. World Archaeology. V. 26(3), pp. 421-441.

Curet, L.A. 2005. Caribbean Paleodemography: Population, Culture-History, and Sociopolitical Processes in Ancient Puerto Rico. University of Alabama Press.

Granberry, J.W. 2005. The Americas That Might Have Been: Native American Social Systems Through Time. University of Alabama Press. 204 pp.

Granberry J.W. and G.S. Vescelius. 2004. Languages of the Pre-Columbian Antilles. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

Guitar, L. 2000. Criollos: The Birth of a Dynamic New Indo-European People and Culture in Hispaniola. Kacike: The Journal of Caribbean Amerindian History and Anthropology. Caribbean Amerindian Centrelink. V. 1, pp. 1-17.

Keegan, W.F. 2013. The “Classic” Taíno. In the Oxford Handbook of Caribbean Archaeology. W.F. Keegan, C.L. Hofman and R.R. Ramos. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 70-83.

Las Casas, B. de. 1999. Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies. Translated by Nigel Griffin. Penguin. London.

Mann, C.C.. 2011. 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created. Alfred A. Knopf. 560 pp.

Mosink, J. 2015. Spanish-Lucayan Interaction: Continuity of Native Economies in Early Historic Times. Journal of Caribbean Archaeology.

Phillips, W.D. and C.R. Phillips. 1993. The Worlds of Christopher Columbus. Cambridge, England.

Ramos, R. R. 2010. Rethinking Puerto Rican Precolonial History. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

Rouse, I. 1992. The Taínos: Rise and Decline of the People Who Greeted Columbus. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Sale, K. 1991. The Conquest of Paradise: Christopher Columbus and the Columbian Legacy. Plume. 464 pp.

Saunders, N.J. 2005. The Peoples of the Caribbean: An Encyclopedia of Archeology and Traditional Culture. ABC-CLIO.

Soto, M.C. 2008. Dissertation: Inhabiting Isla Nena, 1514-2003: Island Narrations, Imperial Dramas and Vieques, Puerto Rico. The University of Michigan.

Zinn, H. 2003. A People’s History of the United States. New York: Perennial Classics. HarperCollins. 729 pp.

It’s arduous to search out knowledgeable people on this topic, however you sound like you already know what you’re talking about! Thanks